The Picture of Dorian Gray – A Complete Analysis

Beauty, Corruption, and the Cost of a Soul

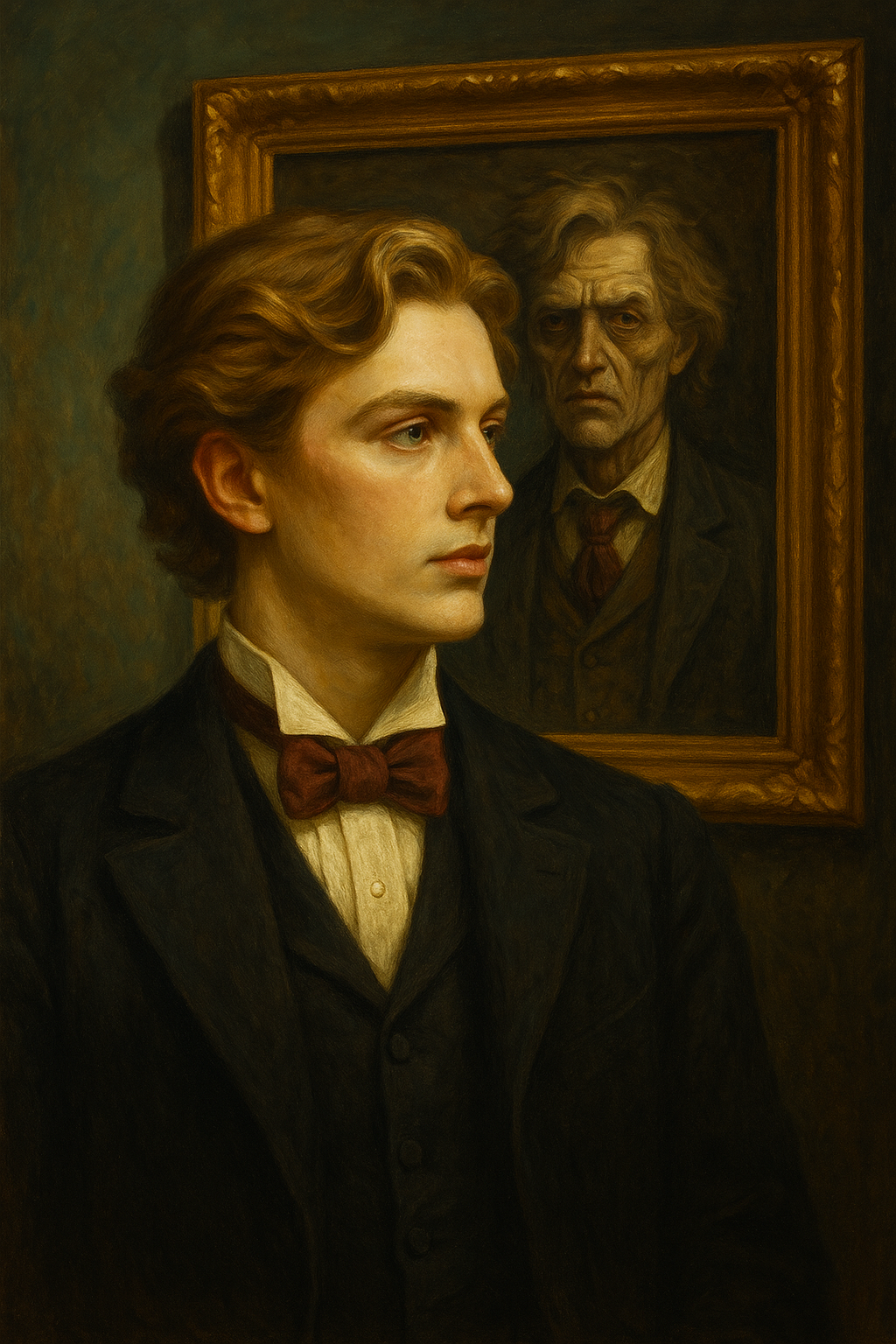

Outwardly perfect, inwardly ruined – the double life of Dorian Gray.

A reader’s guide to The Picture of Dorian Gray – plot, themes, and the dark magic of Wilde’s only novel. This article features a comprehensive Picture of Dorian Gray analysis.

1. The starting point: a beautiful boy and a dangerous idea

The Picture of Dorian Gray begins in an artist’s studio. Basil Hallward, a serious and rather shy painter, has become obsessed with a young man he has been painting: Dorian Gray. Dorian is not just good–looking; he is, in Basil’s eyes, a kind of ideal – beauty, youth, and innocence made flesh. Basil almost worships him, and he is afraid to exhibit the portrait because it reveals too much of his own feelings.

Into this room strolls Lord Henry Wotton, witty, lazy, and extremely dangerous. Henry’s “philosophy” is that life is meant for pleasure, that morality is a boring Victorian invention, and that youth and beauty are the only things worth having. When Dorian arrives, Henry begins to work on him like a sculptor working on marble. He tells Dorian that one day he will grow old and the beauty he takes for granted will be gone forever. That thought hits Dorian like a wound.

In a moment of wild, childish despair, Dorian makes the wish that powers the whole novel: that he himself might stay forever young, and that the portrait should grow old in his place. It feels like a theatrical outburst – but in Wilde’s world, dangerous wishes are granted.

2. The bargain in action: the portrait as a poisoned mirror

At first, nothing seems different. Dorian goes out into London society, dazzled by Lord Henry’s talk and determined to taste everything life can offer. When he meets Sibyl Vane, a young actress who plays Shakespeare heroines in a shabby little theatre, he thinks he has discovered “ideal love”. He calls her his Juliet, his Imogen, his Ophelia. Importantly, he is in love with her performances – with Art – more than with the real girl.

The spell begins to crack when Sibyl falls in love with him as a person. Now that she has “real” love, her acting loses its magic. She can no longer pretend on stage. Dorian is humiliated in front of his sophisticated friends, and he punishes her cruelly. He tells her she has killed his love and ends the engagement. That night, Sibyl kills herself.

When Dorian returns home, he sees something impossible: the mouth in the portrait has twisted into a faint, ugly sneer. The canvas is recording the corruption of his soul. Physically, Dorian remains as beautiful as ever. It is the painted Dorian who begins to age, to harden, to become cruel. Terrified but fascinated, Dorian hides the portrait in an upstairs room and continues his life of pleasure, comforted by the thought that his sins will never show on his own body.

3. Descent: pleasure, reputation, and the rotting of the self

From here the novel jumps forward in time. Years pass, but Dorian’s face stays young. London, however, begins to whisper. Men who know him lose jobs, money, or reputation. Young people who fall under his charm somehow come away stained. Wilde never lists every “sin” – that would be dull. Instead he gives us hints: opium dens, mysterious friendships, rumours of cruelty and blackmail.

Outwardly, Dorian still attends fashionable dinners and collects art and jewels; he is the perfect gentleman. Inwardly, he is hooked on the thrill of getting away with it. Each time he does something shameful and sees the portrait grow uglier – the eyes bloodshot, the hands stained, the flesh coarsening – he is both disgusted and fascinated. The painting is his secret self, the evidence that he still has a conscience, however damaged.

Only Basil, the painter, dares to confront him. Hearing the rumours, he begs Dorian to pray, to turn his life around. In a moment of fury, Dorian drags Basil upstairs and forces him to look at the portrait. Basil is horrified. He sees what his art has become: not a celebration of beauty, but a record of monstrous corruption. In a rage of self–hatred, Dorian kills him. The man who first worshipped Dorian’s beauty becomes his most direct victim.

4. Themes: beauty, morality, and the Victorian double life

a) Beauty and the body

Wilde was obsessed with beauty: clothes, voices, faces, furniture, language. The novel asks a simple but savage question: what happens if you treat beauty as the only standard that matters? Dorian’s face and figure give him social power. People excuse what he does because he looks innocent. Lord Henry’s philosophy – “the only way to get rid of a temptation is to yield to it” – sounds glamorous, but in practice it turns Dorian into a hollow man, addicted to sensation.

The portrait flips the usual moral lesson. Instead of “sin leaves marks on the body”, Wilde imagines sin leaving marks on a hidden canvas. The world sees an angel; the attic hides the truth.

b) Art and morality

In the famous preface, Wilde writes that “there is no such thing as a moral or an immoral book. Books are well written, or badly written. That is all.” Yet the story that follows is full of moral consequences. One way to read this is that Wilde is teasing the Victorians: they want art to teach “lessons”, but he gives them a beautiful nightmare instead.

The portrait is both a work of art and a kind of ethical X–ray. It shows that art cannot be totally separated from life; the way we live changes how we experience beauty. Basil paints the portrait out of sincere, almost sacred admiration. Dorian turns it into a private horror museum. Lord Henry treats life itself as art, something to be “composed” without worrying about the people who get hurt.

c) Hypocrisy and the hidden self

Victorian society loved appearances: a respectable home, clean clothes, calm manners. Underneath that surface were secret clubs, double lives, and intense fears about scandal. Dorian embodies this split. His drawing–room self is charming, generous, almost saintly. His attic self, on the canvas, is vicious and decayed.

Wilde knew this pattern personally. As a queer man in a homophobic culture, he understood what it meant to have desires you could not admit publicly. The Picture of Dorian Gray is not just a moral fable; it is also a coded story about the pressure to hide who you are – and what that hiding can do to a person’s mind.

5. The ending: trying to destroy the evidence

After Basil’s murder, the circle tightens. James Vane, Sibyl’s brother, hunts Dorian, convinced that this eternally young man must somehow be responsible for his sister’s death years earlier. Dorian escapes almost by accident when James is killed in a shooting accident, but the shock shakes him. For a moment, he wonders if he could become “good” again and reverse the damage on the portrait.

He tries one small act of mercy with a country girl, refusing to seduce her as he normally might. When he rushes back to the attic, hoping to see the picture softened, he finds it even worse: the mouth more hypocritical, the expression smug. Dorian learns that wanting to seem good – to admire his own reform – is just another form of vanity. He does not truly repent; he only wants a prettier conscience.

In a last, furious attempt to free himself, Dorian takes the same knife he used on Basil and stabs the portrait. Servants hear a scream. When they break into the locked room, they find the painting restored to its original youth and beauty. On the floor lies a dead old man, hideous and wrinkled, with a knife in his heart. Only by his rings can they recognise him as Dorian Gray.

The novel ends where it began – with a work of art – but the roles are reversed. The portrait is now pure and untouched; the real body bears the full weight of years of corruption. The bill has finally been presented.

6. Why Dorian Gray still matters

Modern readers live in a world of filters, profile pictures, and carefully edited versions of ourselves. Wilde’s story feels oddly prophetic. Dorian Gray is the ultimate “curated image”: he edits reality so that only his flattering surface is visible. The portrait in the locked room is everything he tries not to show – guilt, shame, damage, fear.

The novel asks questions that still sting:

What would our own “portrait” look like if every choice left a visible mark somewhere? How much harm can be hidden behind charm, wealth, or beauty? Can you truly start again, or do you eventually have to face what you have done?

Wilde never preaches directly; he wraps the darkness in glittering talk and gorgeous descriptions. That mixture is what makes The Picture of Dorian Gray so unsettling. It is not a dry Victorian sermon. It is a seductive invitation to enjoy beauty – while quietly showing the cost of worshipping beauty alone.

For students, the novel is a treasure chest: Gothic horror, psychological drama, queer subtext, a satire of upper–class London, and a meditation on art itself. For Wilde, it was also risky autobiography in disguise. Dorian destroys the portrait that tells the truth about him. Wilde, more bravely, published his.

Essential Reading: Editions and Study Guides

Recommended Editions:

- The Picture of Dorian Gray (Dover Thrift Edition) – The most affordable edition, perfect for students and first-time readers

- The Picture of Dorian Gray: An Annotated, Uncensored Edition by Nicholas Frankel – The uncensored original text with extensive annotations revealing the novel’s coded meanings

For Students:

- Study Guide: The Picture of Dorian Gray (SuperSummary) – Chapter summaries, theme analysis, and discussion questions

- The Picture of Dorian Gray (Academic Edition) – Complete text with introduction, study guide, and chapter quizzes

Whether you’re reading for pleasure, studying for exams, or leading a book club discussion, these editions offer everything you need to engage deeply with Wilde’s masterpiece.

This analysis of The Picture of Dorian Gray serves as a critical examination of the novel, revealing the layers of meaning within Wilde’s work.