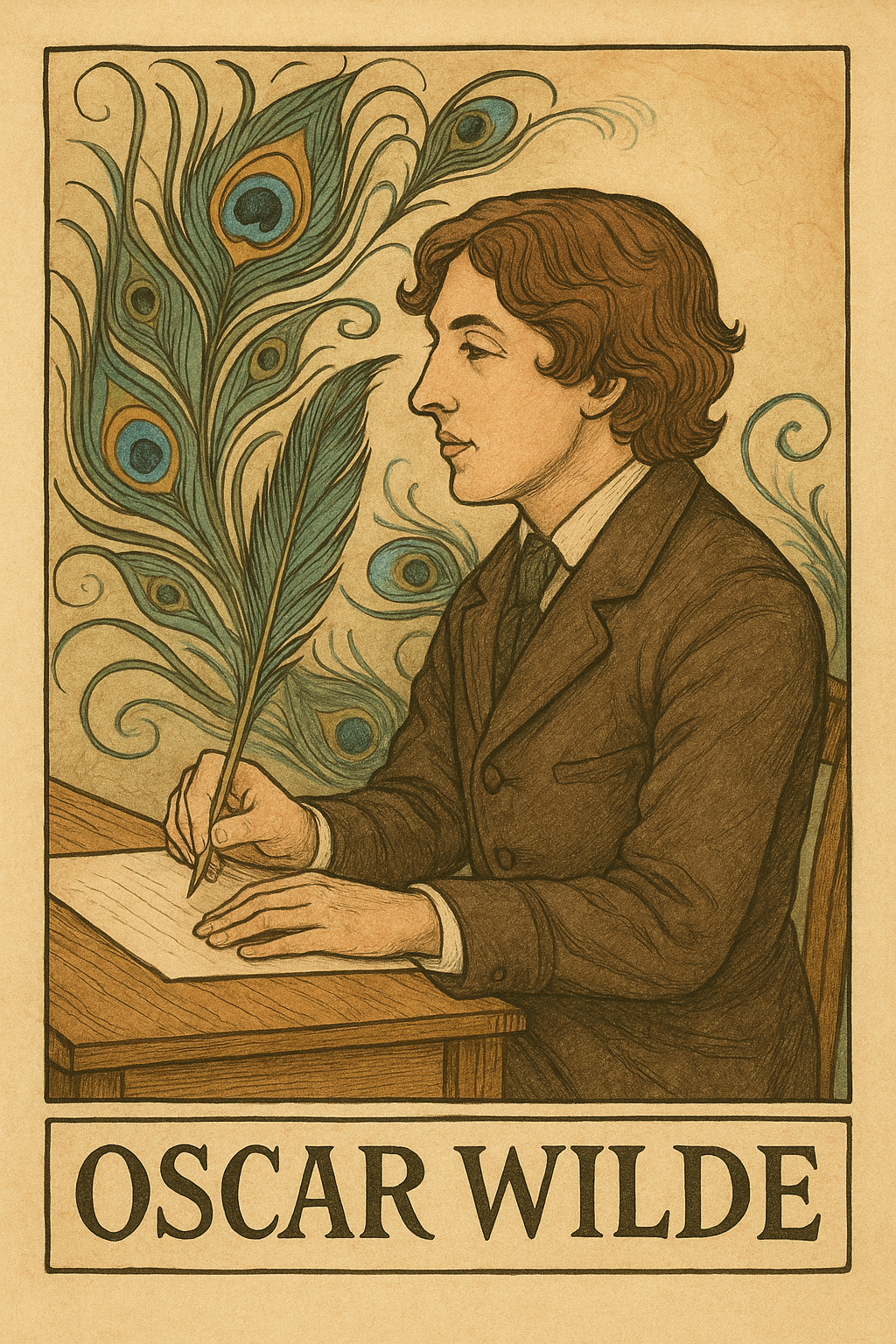

Oscar Wilde’s School Days, Trinity & Oxford: The Making of a Genius

Before the epigrams, the lilies, and the scandals, there was a boy in a school uniform learning Latin verbs in rainy Enniskillen. Wilde did not step fully formed onto the London stage: he was made, slowly and awkwardly, in classrooms and common rooms from Portora to Trinity to Magdalen. This is the story of how Oscar became Wilde.

Portora Royal School: A Classical Education in the Rain

Oscar Wilde’s story as a student begins far from the glittering West End, at Portora Royal School in Enniskillen. It was a respectable, rather stern boarding school, where boys in stiff uniforms marched through the usual Victorian disciplines: Latin, Greek, mathematics, scripture, and the art of not answering back.

Wilde, even as a teenager, stood slightly sideways to all of this. He was clever – indisputably so – but he was also dreamy, slow to hurry, and far more interested in the music of a sentence than in the mechanics of a timetable. While Portora drilled boys into clergymen, doctors and civil servants, Oscar quietly rehearsed for something stranger: the role of artist.

The school gave him the tools he would later subvert. Long afternoons with Homer and Virgil sharpened his ear for cadence. Translation exercises taught him how to turn one language into another with precision and flair. He learned how ancient heroes spoke, loved, and argued – knowledge he would smuggle into the sparkling drawing-room comedies of the 1890s.

School Days: The Masters Who Shaped a Genius

Oscar Wilde’s early education has often been overshadowed by the glamour of his Oxford years, but the foundations of his mind — the wit, the love of languages, the showman’s instinct for style — were shaped far earlier. Wilde grew up in a household of intellectual voltage: his mother, “Speranza,” was a revolutionary poet, and his father, Sir William Wilde, was a surgeon, folklorist, polyglot, and lecturer. The Wilde children breathed books like air.

At Portora Royal School in Enniskillen, Wilde quickly distinguished himself not by athletic talent (he was famously hopeless at sports) but by dazzling academic ability. His masters noticed immediately that Wilde possessed an unusual combination: a prodigious memory, a rare ear for language, and a mischievous wit that emerged even in translations and school essays.

One of the earliest and strongest influences was Rev. James Dougherty, the classical master. Dougherty’s method was strict but expansive: not just rote Latin and Greek, but the worldview inside the texts. Wilde later joked that he learned more moral philosophy from Homer than from all Victorian sermons combined — and Dougherty was the one who taught him to hear those voices.

Another formative figure was Mr. Noble, a master who encouraged Wilde’s first attempts at writing. Noble recognised both the child’s brilliance and his theatrical self-display, once remarking that Wilde “never answered a question without performing it.” Encouragement from Noble helped Wilde win multiple school prizes and, crucially, believe that literature could be a life rather than just a subject.

Yet Wilde’s most critical mentor of the period was the man who would follow him into early adulthood: John Pentland Mahaffy. Mahaffy, often called “the last great talker of Europe,” was a classicist, traveller, wit, and social tactician. Wilde adored him — and studied him. Mahaffy taught Wilde how to converse, how to charm, how to deploy quotation and paradox like weapons. It is impossible to understand Wilde’s later salon brilliance without understanding Mahaffy’s tutorials.

Mahaffy also cultivated Wilde’s taste for Greece. He didn’t just teach him the language; he taught him a nostalgia for a civilisation Wilde had never seen. Years later, Wilde would say: “If Mahaffy had walked into the Louvre with me, all art would have been a living conversation.” That mixture of classical philosophy, wit, and beauty was already cooking in Wilde long before Oxford — and Mahaffy was the chef.

Under their guidance, Wilde became one of Portora’s star pupils, winning the Carpenter Prize for Greek and a coveted scholarship to Trinity College, Dublin. By the time he arrived at Trinity, Wilde’s intellectual muscles were already tuned for performance — and the world was ready for the glittering undergraduate he would become.

Books, Loneliness, and the Outsider’s Eye

Portora also gave Wilde something less glamorous but just as important: long, lonely stretches of time. School can be a brutal place for the odd, the sensitive, or the boy who prefers a book to a rugby ball. Wilde was not completely friendless, but neither was he the hearty, games-loving Victorian ideal. That slight distance from the pack may have hurt at the time, but it gave him what every future satirist needs – an outsider’s eye.

From this vantage point he watched schoolmasters, prefects, and cliques with quiet amusement. Years later, the same cool, amused gaze would fall on London society: on its marriages and its hypocrisies, on its carefully ironed morals and badly hidden secrets. The seed of The Importance of Being Earnest is already there in the schoolboy who learns to read the gap between what people say and what they are.

Home, “The Museum,” and the Pressure to Shine

Whenever Oscar left Portora and returned to Dublin, he stepped into a very different kind of classroom: his own home. The Wildes’ house in Merrion Square was dubbed “The Museum” for its shelves of books, its medical specimens, its art, and its stream of visitors. Sir William Wilde brought the authority of science; Lady “Speranza” Wilde brought poetry, nationalism, and the intoxicating belief that words could change the world.

The result? A boy who was expected to be brilliant. This pressure could be heavy, but it also gave Wilde the confidence to treat intellectual ambition as natural, almost inevitable. When other boys dreamed of careers in the Church or the civil service, he was already being nudged toward the life of the mind.

Trinity College Dublin: Learning to Live in Two Worlds

In 1871 Wilde moved on to Trinity College Dublin, winning a scholarship and beginning to turn promise into performance. If Portora had taught him how to endure a curriculum, Trinity taught him how to flourish within one – and occasionally how to bend it to his will.

Trinity offered a richer intellectual diet: philosophy, literature, philology, the history of ideas. Wilde shone in classics and immersed himself in the Greek world that would leave so deep a mark on his imagination. The gods, heroes, and myths of antiquity gave him a language for beauty and desire that felt more honest – and far more glamorous – than the moralistic tone of Victorian sermons.

Scholarship by Day, Salon by Night

To imagine Wilde at Trinity is to picture a young man moving between two overlapping worlds. By day, he is the serious scholar: attending lectures, reading in the library, translating, competing for prizes. By night, he becomes the social performer: talking, joking, telling stories, and discovering the power of his own voice in small student circles.

This double life would become a pattern. Wilde always lived at the intersection of the studious and the theatrical, the library and the stage. Trinity gave him a first taste of that balance. He learned that ideas did not have to stay safely locked inside essays; they could be worn like flowers in a buttonhole, tossed into conversation, or turned into a dazzling remark over dinner.

Winning Doors, Opening Others

Wilde’s achievements at Trinity were not merely charming; they were concrete and impressive. He won distinction in classics and secured a scholarship that opened the door to the next, more famous stage of his education. In a Victorian world where class and money were obstacles, prizes and scholarships were golden keys. Wilde used them with style.

That path led across the Irish Sea to a place that would become central to his myth: not just Oxford, but a particular corner of it – Magdalen College, with its cloisters, deer park, and air of almost unreal calm.

Oxford: Magdalen, Aestheticism, and the Invention of “Oscar Wilde”

Wilde arrived at Magdalen College, Oxford in 1874. If Portora had trained him and Trinity had polished him, Oxford would do something more radical: it would give him permission to invent himself.

Oxford, in the 1870s, was a place where storms of thought were passing through the calm of ancient stone. Two figures mattered above all for Wilde: John Ruskin and Walter Pater. Between them, they pulled his imagination in two powerful directions.

Ruskin & Pater: Two Voices in His Ear

Ruskin, moralist and art critic, believed that beauty was never detached from duty. Art, for him, was a serious business that ought to make people better, kinder, more aware of social injustice. Wilde absorbed Ruskin’s vision through works like The Stones of Venice, where Gothic architecture became a moral text about honest labour and true craftsmanship, and Unto This Last, Ruskin’s radical essay arguing that economics, art, and science must rest on a foundation of morality. Under Ruskin’s guidance, Wilde even took part in a project to build a road with his own hands – a lesson in the dignity of labour that must have felt very far from future drawing-room epigrams.

Pater, by contrast, whispered a more seductive gospel: that life is short, intense, and best lived in moments of sharpened sensation and perception. His Studies in the History of the Renaissance suggested that the aim of life was not merely to behave well, but to experience deeply – to “burn with a hard, gem-like flame.” That famous phrase, from the book’s notorious Conclusion, became a kind of aesthetic battle cry for Wilde’s generation. Pater’s Selected Essays and later writings on art deepened this philosophy, offering Wilde a way of thinking about beauty that was unapologetically sensual and self-justifying.

Wilde absorbed both voices, and the tension between them runs through his work. In The Picture of Dorian Gray, we hear Pater in Lord Henry’s shimmering speeches about pleasure and youth; we hear Ruskin in the brutal consequences that follow when beauty is severed entirely from conscience. Oxford gave Wilde not one philosophy, but a lifelong argument between two.

The Scholar Who Loved Applause

It is easy to imagine Wilde at Oxford as purely a dandy in embryo, strolling among the cloisters in long hair and languid poses. But beneath the legend was a formidable student. He read widely, produced essays, competed for prizes, and in 1878 won the prestigious Newdigate Prize for his poem “Ravenna.”

That prize matters for more than its line on a CV. It shows Wilde learning that his seriousness and his showmanship did not have to cancel each other out. He could be both: the rigorous classicist and the young man who knows just how to make an audience listen. The blend of intellect and performance that later electrified London had already been tested on an Oxford stage.

Inventing the Aesthete

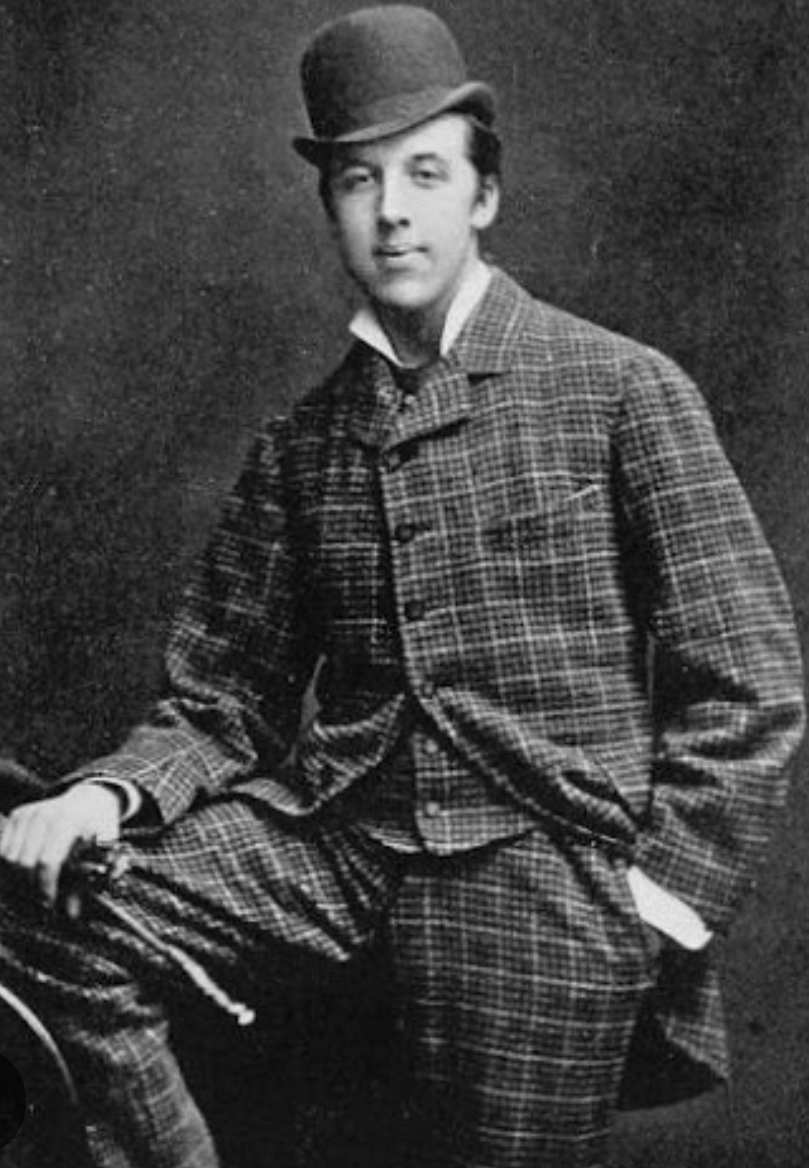

Oxford was also where Wilde began to consciously cultivate what we might now call a “brand.” He decorated his rooms with blue china, wore clothes that were just a fraction too singular for ordinary taste, and spoke about art and beauty with a seriousness that some found inspiring and others absurd. In doing so, he turned himself into an advertisement for a way of living: the life of the aesthete.

This was not superficial vanity; it was a kind of experiment. Wilde was testing how far a person could make life into art – how far the self could be written and rewritten, like a play. The shy schoolboy of Portora had been replaced by a young man who knew that attention could be used as a tool, even a weapon.

That self-invention would later carry him to America on a lecture tour, into marriage with Constance, into the salons of London, and, tragically, into the courts. But its roots are here: a student among the cloisters, half sincerely devoted to beauty, half delighting in the role of “Oscar Wilde” that he was learning to play.

From Schoolboy to “Wilde”: Why These Years Matter

Why dwell on school reports and scholarship prizes when Wilde’s later life offers scandal, trials, and immortal one-liners? Because without understanding his formation at Portora, Trinity, and Oxford, we risk treating Wilde as a meteor flashing briefly across the Victorian sky – brilliant but inexplicable.

In reality, his genius was patiently built:

- Portora gave him classical discipline, loneliness, and the outsider’s eye.

- Trinity gave him confidence, scholarly distinction, and the sense that ideas could be lived as well as studied.

- Oxford gave him philosophies to wrestle with, a persona to inhabit, and a first taste of public fame.

By the time Wilde left Oxford, the essentials were in place. He had a style, a set of obsessions, a gift for performance, and a deep familiarity with the classical tradition that would haunt everything he wrote. The dazzling London playwright, the author of Dorian Gray, the doomed defendant in the dock – all of them are contained, in miniature, in the boy bent over his Latin grammar and the young man listening to Pater in an Oxford lecture room.

To read Wilde’s school and university years is to see that brilliance is rarely pure, and never simple. It is made of homework and heartache, prizes and pressures, afternoons in the library and evenings in conversation. Rome wasn’t built in a day; neither was Oscar Wilde.

Oscar Wilde school days were foundational in shaping his literary genius.

Oscar Wilde school days were filled with unique experiences that influenced his later works.

Oscar Wilde’s school days were filled with unique experiences that influenced his later works.

Oscar Wilde school days were foundational in shaping his literary genius.

Further Reading & Resources

If you want to explore Oscar Wilde’s formative years in greater depth, these books offer invaluable insights into how the schoolboy became the genius:

- Oscar Wilde by Richard Ellmann – The classic, compassionate Pulitzer Prize-winning biography with extensive coverage of Wilde’s education at Portora, Trinity, and Oxford

- Oscar Wilde: A Life by Matthew Sturgis – The most comprehensive modern biography, drawing on newly discovered materials to portray Wilde’s school years in rich detail

Related Articles

- Lady Speranza Wilde: Poet, Patriot, and Mother of a Legend

- Constance Wilde: Author, Mother, and the Woman Behind Oscar Wilde’s Legend

- Sir William Wilde: Scandal, Silence, and the Shadow Over Oscar

Wilde Reflections ✒️✨

“Every story deserves a reply — even those told in wit, wounds, and Wilde.”

Share your reflection, question, or favourite line below.